Editor’s Note: Virtual reality has become the latest frontier in the quest for visual escapism. In the 19th century the same concept was sought in a technological gizmo that swept the nation as early as the 1850s—stereography. The exhibition East of the Mississippi: Nineteenth-Century American Landscape Photography includes two stereoscopes and numerous stereographs. The museum invites visitors to engage these antiquated devices and time travel across the centuries.

The 1851 world’s fair in London, officially known as the The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, featured a dazzling array of technological innovations displayed in a massive steel-and-glass pavilion known as the Crystal Palace. Over the course of six months, more than six million ticket-buyers were awed by such marvels as Bakewell’s “image telegraph” (a precursor to today’s fax machine), a McCormick’s grain reaper shipped directly from the factory floor in Chicago, a “tempest prognosticator” that monitored the motion of leeches in a tube of rainwater to predict approaching storms, and the first-ever pay flush toilets for a public building. Queen Victoria herself was duly impressed by a display floor brimming with “every conceivable invention,” but one attraction caught her eye, quite literally—a newfangled novelty known as the stereoscope.

By placing one’s eyes in the viewing lens of this wooden contraption that held a photographic card of side-by-side duplicate images, binocular vision transformed the print into a three-dimensional scene. The first stereoscope was credited to Sir Charles Wheatstone in 1838—the year of photography’s birth—a viewing device that initially used angled mirrors to convey drawn illustrations. The product’s name, of Greek derivation, implies the ability to see something as a “solid body.” The device was improved upon in 1844 by Scottish physicist David Brewster whose use of prisms instead of mirrors also led to the invention of the kaleidoscope. Pioneering French photographer Jules Duboscq, renowned for the high quality of his optical instruments, established a booth of stereoscopic equipment at the London exposition. The British monarch’s gleeful attention to such wares would soon launch an international craze for a handheld, nonmechanical device that would effortlessly bring the wonders of the world into the domestic environs of middle-class Britons and Americans alike. By 1856 more than a half million stereoscopes had been sold on both sides of the Atlantic.

American intellectual and ambitious tinkerer Oliver Wendell Holmes further altered the viewing apparatus by creating his “stereopticon” in 1859, which became a fixture in fashionable parlors nationwide, ultimately dominating the market from the 1880s through the 1940s. Holmes wrote in the Atlantic Monthly of June 1859 that “the first effect of looking at a good photograph through the stereoscope is a surprise such as no painting ever produced. The mind feels its way into the very depths of the picture. The scraggy branches of a tree in the foreground run out at us as if they would scratch our eyes out. The elbow of a figure stands forth as to make us almost uncomfortable.”

Large companies such as Negretti & Zambra, Underwood & Underwood, and the Keystone View Company were soon dispatching photographers around the world to capture scenes previously known to most only through the pages of books or as illustrations in newspapers and magazines. From the Taj Mahal and the Great Pyramids of Giza, to the new skyscrapers of New York and newly laid track of expanding railroads, ancient and modern engineering wonders alike were visible to those unable to travel prohibitive distances at great expense.

Curator Russell Lord explains, “While photography, in general, often provided access to the inaccessible, stereographs provided a palpable experience of far-away places, transforming the ‘there and then’ to the ‘here and now.'”

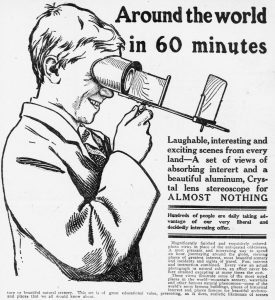

Natural disasters also drew voyeuristic interest. Stereocards of the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, the Galveston hurricane of 1900, and the 1906 San Francisco earthquake became big sellers. Early advertisements for stereopticons promised “laughable, interesting, and exotic scenes from every land” and “a tour of the world for only 75-cents,” with an assurance of “nothing vulgar or displeasing.”

School classrooms became a lucrative market, too. “The stereograph is a superior kind of text, and a good teacher will not have so much trust in mere print,” wrote the Underwood & Underwood company in its teacher manual, The World Visualized for the Classroom. Testified one teacher, “It may not be too sanguine to believe that a child may be made thus to know more of the real life of foreign or of distant lands than is often known by the hasty or careless traveler who visits them.”

East of the Mississippi: Nineteenth-Century American Landscape Photography includes two stereoscopes for public use and a display of twenty-six stereocards, ranging in content from a contemplative man beneath a live oak tree to a tightrope walker crossing the raging rapids in the river flowing from Niagara Falls. As explained in an exhibition panel written by Russell Lord: “Comparatively inexpensive, the stereograph created a mass market for landscape views and allowed an ‘armchair traveler’ to visually explore other parts of the country.”

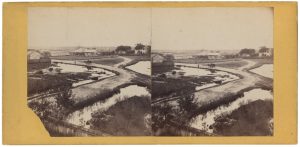

Theodore Lilienthal, Bird’s-Eye View from Moreau’s Restaurant, Mouth of Bayou St. John, 1867, stereoscopic albumen prints, The Historic New Orleans Collection

There were also critics of the popular distraction. French poet Baudeliere decried “a thousand hungry eyes…bending over the peep-holes of the stereoscope, as though they were attic-windows of the infinite.”

The stereoscope waned in popularity as motion pictures became a popular form of visual entertainment, but the phenomenon morphed into the popular View-Master toy which debuted at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York by Sawyer’s, a photo-finishing company. Round disks of 3-D color photographs slotted into a plastic viewing device that rotated the images by an internal lever were sold as an alternative to souvenir postcards. To date, more than 1.5 billion View-Master reels have been sold worldwide.

In 1987, computer scientist Jaron Lanier coined a new term for this quest for this visual out-of-body experience—”virtual reality”—and new technology continues to perfect mental escapism. Lanier partnered with fellow Atari colleague Thomas G. Zimmerman to form VPL Research, Inc., the first company to sell virtual-reality goggles and gloves. In 2015, the New York Times Magazine launched a virtual-reality app that presents such immersive, vicarious experiences as being embedded with Iraqi soldiers fighting ISIS, traversing the Antarctic icecap and the surface of Pluto, and climbing the spire of the New York’s Freedom Tower with professional mountaineer Jimmy Chin. The riveting scenes may be viewed on a rudimentary cardboard device with two eyeholes, manufactured by Google, that easily slips over a smartphone.

As Palmer Luckey, founder of Oculus VR has said, “If you have perfect virtual reality eventually, where you’re able to simulate everything that a person can experience or imagine experiencing, it’s hard to imagine where you’ll go from there.”

—David Johnson, Editor of Museum Publications